We had nineteen family members to Thanksgiving dinner. They were all on Ben's side - parents, step-parents, siblings, nephews, cousins, even an aunt. These are people that I have known for many years now, people I feel close to, people I consider my family. In many ways, Ben's family has supplied the extended family for mine. My father is gone, my mother is, too, for all intents and purposes. My sister has long since forged her own path away. My brother, thankfully, my dear brother, is here. Jean-Paul and his wife, Tracy, and my two small nephews live one town over. Tracy was brought up in Michigan. Her adoptive parents are still there and rarely make it west. And so Ben's parents - all four of them - have stepped in as grandparents to my brother's boys. We spend every holiday all together. It's an amiable bunch.

This Thanksgiving, JP and Tracy decided to spend the day on their own with their boys. I was fully in support of the idea. I love the family holiday but I also love to live without obligation, as much as possible. The fact that we choose to be together is part of what makes it so special. Also, the idea that I could, one holiday season, cut the cord and go, say, to the Caribbean with Ben and the kids is also appealing.

When my mother went into assisted living, I cleaned out her house. I boxed fifty years of family in three woozy days. I touched all the objects I had known all my life. Objects that may have only been lamps and plates and figurines but were, for me, icons. Some went to Goodwill. Most, including my parents' beautiful mid-century Scandinavian furniture, went to me. My siblings didn't have room. I had a new mid-century house that needed exactly these objects. And, perhaps more deeply, the presence of these things, these bits of my childhood, was comforting.

And so my kids sit at the same table I did when I was their age. Their feet dangle from the same chairs, their crumbs fall in the same crevices. It makes for a lot of deja-vu.

It wasn't until I was layering slices of homemade bread in concentric circles on my mother's wooden plate on Thursday, the very same plate on which she layered homemade bread in concentric circles, that it hit me. Here on Thanksgiving, for the first time ever, I was the only one present of my original five. I felt a rush of homesickness for my mama, for my family, for what was.

My parents were married on Thanksgiving. November 25th, 1954, the very same year our current house was built. And in this house, on Thanksgiving, on November 25th no less, a family gathered around their table. We carved the turkey with their carving knife. We passed stuffing and gravy and potatoes in their serving bowls. Everything was here but them.

I have a new five. A loving and ever-fascinating husband I don't know how I had the wisdom to select after kissing so very many frogs. And these three children, these three that I would do anything for. That, in my worst nightmares, I am separated from. We five sat around that old table, together, surrounded by our family. Not the family I was born into but my family all the same. I raised a toast to my parents, to their marriage, to their anniversary. We all raised their glasses and drank.

Tuesday, November 30, 2010

Monday, November 22, 2010

That Black Kid

I was at the park the other day, happily reading a book about Columbine, the kids somewhere out of sight, when I heard a child say, "That black kid just smacked me in the face."

I looked toward the voice and saw a blond girl, probably about seven, standing on the next bench over, reporting her news over the fence to an adult and a couple other kids.

This was discouraging for a number of reasons. The first one being, she could only be talking about Mihiretu. He was the sole black kid for miles around. At some point soon I'm going to have to address the ridiculous lack of diversity in my beloved corner of the earth.

Secondly, she identified him as "that black kid". Not "that African-American kid". Not "that kid". I use "black" myself on occasion but usually semi-ironically, as in "What's that little black boy doing in our living-room?" Immediately, and assuredly incorrectly, I imagined her parents sprawled on their aging plaid couch, scratching their crotches as they reached for another Bud Light, complaining about "the blacks".

Then there was the general parenting problem of the fact that my kid just probably smacked someone in the face. Mihiretu, at this point, uses his hands to solve arguments no more or less than the next four-year-old but he was undoubtably rightly accused.

I regretfully returned my book to my bag and set off in search of my small band of houligans. As I sidled by the girl, who was still milking the drama of her assault, I shot her a bit of a stink eye. She didn't see me, she certainly didn't deserve my scorn, but I had to throw up a bit of psychic protection around that black kid. My black kid.

I looked toward the voice and saw a blond girl, probably about seven, standing on the next bench over, reporting her news over the fence to an adult and a couple other kids.

This was discouraging for a number of reasons. The first one being, she could only be talking about Mihiretu. He was the sole black kid for miles around. At some point soon I'm going to have to address the ridiculous lack of diversity in my beloved corner of the earth.

Secondly, she identified him as "that black kid". Not "that African-American kid". Not "that kid". I use "black" myself on occasion but usually semi-ironically, as in "What's that little black boy doing in our living-room?" Immediately, and assuredly incorrectly, I imagined her parents sprawled on their aging plaid couch, scratching their crotches as they reached for another Bud Light, complaining about "the blacks".

Then there was the general parenting problem of the fact that my kid just probably smacked someone in the face. Mihiretu, at this point, uses his hands to solve arguments no more or less than the next four-year-old but he was undoubtably rightly accused.

I regretfully returned my book to my bag and set off in search of my small band of houligans. As I sidled by the girl, who was still milking the drama of her assault, I shot her a bit of a stink eye. She didn't see me, she certainly didn't deserve my scorn, but I had to throw up a bit of psychic protection around that black kid. My black kid.

Monday, November 15, 2010

The Morning Drill

Since the time change, our early mornings have gotten earlier. My practice with the kids in years past has been to ignore the time change in either direction. In the summer their bedtime is an hour later, in the winter an hour earlier. Our winter rhythm is school-focused, cozy, sleepy. Our summer rhythm is more social, more outdoor, looser.

Because of this practice, however, Mihiretu, who, having shed his nap, retires early, is now waking up in the five o'clock hour. There were a couple of mornings last week that started at four-thirty. Ben and I also go to bed early so it's not as crippling as it could be, but it does make for a whole lot of morning. By the time we're riding bikes to school at 8:45, the day seems half over.

The upside of this long morning is there's ample time to complete the morning chores. Though, from the moment I open my eyes to the moment the front door swings shut behind me, I'm hustling. Making beds, making breakfast, making lunches, feeding the children, the cat, the guinea pigs and the chickens, bathing and clothing the kids and myself, grooming everyone's hair, brushing teeth, washing breakfast dishes, tidying up toys brought out for morning play and then, if I'm feeling ambitious, applying mascara - only to myself.

I looked at the row of packed lunches this morning and felt a wave of accomplishment, then an accompanying wave of embarrassment. Really? I'm proud of getting the lunches made? But then I thought, well, okay, maybe making lunches in and of itself isn't a big deal, but when you add that to the hundreds of other small gestures of nurture I make in a day, not only the chores but the small kindnesses, each gift of praise, it probably makes up a bigger picture. A picture of a family that's well cared for.

Maybe these incredibly busy years, these years chock full of boring tasks, of laundry, groceries, mopping up spills of all varieties, wiping noses and bottoms, enforcing homework and bedtime and general non-violence, these years of drudgery, are my most impactful. Maybe this, these lunches lined up on a counter, are my legacy. My effort at raising kids that feel loved in big ways and small, kids who will maybe go on to become happy and healthy adults. Adults who might do some good in the world. Or, at very least, be good parents.

Sometimes - often - all I want to do is turn my back on the vacuum and the laundry basket, the mewling cat and the screaming child, and curl up alone with a book. But when I see Mae poised so confidently on the stage at school, calmly reading the list of Halloween costume victors, or Lana quickly and correctly answering Mae's multiplication homework, or Mihiretu tentatively emerging from his protective chrysalis, unfolding himself, revealing his delicate, multicolored wings, actually risking our love, it seems like I am maybe doing something right. Maybe a few somethings. Maybe all those pennies dropped in the jar are adding up.

Worth getting up at 4:30 in the morning. Most days.

Because of this practice, however, Mihiretu, who, having shed his nap, retires early, is now waking up in the five o'clock hour. There were a couple of mornings last week that started at four-thirty. Ben and I also go to bed early so it's not as crippling as it could be, but it does make for a whole lot of morning. By the time we're riding bikes to school at 8:45, the day seems half over.

The upside of this long morning is there's ample time to complete the morning chores. Though, from the moment I open my eyes to the moment the front door swings shut behind me, I'm hustling. Making beds, making breakfast, making lunches, feeding the children, the cat, the guinea pigs and the chickens, bathing and clothing the kids and myself, grooming everyone's hair, brushing teeth, washing breakfast dishes, tidying up toys brought out for morning play and then, if I'm feeling ambitious, applying mascara - only to myself.

I looked at the row of packed lunches this morning and felt a wave of accomplishment, then an accompanying wave of embarrassment. Really? I'm proud of getting the lunches made? But then I thought, well, okay, maybe making lunches in and of itself isn't a big deal, but when you add that to the hundreds of other small gestures of nurture I make in a day, not only the chores but the small kindnesses, each gift of praise, it probably makes up a bigger picture. A picture of a family that's well cared for.

Maybe these incredibly busy years, these years chock full of boring tasks, of laundry, groceries, mopping up spills of all varieties, wiping noses and bottoms, enforcing homework and bedtime and general non-violence, these years of drudgery, are my most impactful. Maybe this, these lunches lined up on a counter, are my legacy. My effort at raising kids that feel loved in big ways and small, kids who will maybe go on to become happy and healthy adults. Adults who might do some good in the world. Or, at very least, be good parents.

Sometimes - often - all I want to do is turn my back on the vacuum and the laundry basket, the mewling cat and the screaming child, and curl up alone with a book. But when I see Mae poised so confidently on the stage at school, calmly reading the list of Halloween costume victors, or Lana quickly and correctly answering Mae's multiplication homework, or Mihiretu tentatively emerging from his protective chrysalis, unfolding himself, revealing his delicate, multicolored wings, actually risking our love, it seems like I am maybe doing something right. Maybe a few somethings. Maybe all those pennies dropped in the jar are adding up.

Worth getting up at 4:30 in the morning. Most days.

Friday, November 5, 2010

Ingrid Betancourt

I was listening to Ingrid Betancourt the other day on NPR. She's the woman who, while campaigning for the Columbian presidency, was taken captive by the FARC and held for six years. Fascinating, without a doubt, the whole story, but one aspect of her tale particularly struck me. When she was kidnapped, her children were fourteen and sixteen. It's horrible in any case to be separated from your loved ones for any period, let alone six years, but the thought of these children that still needed their mother, who weren't done growing up, waiting and worrying for so long really got me. Ingrid, herself, said that those six years, those years of torture, of isolation, of sitting chained, quite literally, to a tree, made some things very clear. She had been fighting the good political fight for Columbia for years but she was more than ready to let that go. The only thing she was determined to return to, the only thing, she realized, that made her happy, was being a mother. I don't know what the hell that says for feminism but I feel the same way.

Later that day, I was in the van with the kids, headed for Ben's dads' house to carve pumpkins. It was a rare moment in the car that they weren't screaming at each other or swinging fists so I took advantage of the seat-belts holding them in place, my little captive audience, and told them about Ingrid Betancourt and what she had learned. And I told them that the one thing in my life that makes me happiest, by far, is being their mother. I may complain, I may get grumpy, I may even yell but always, underneath it all, I'm so grateful to be able to be home with them, to nurture them, to watch them grow. Them, particularly, those three disparate, complicated creatures. That I'm lucky to be their mom.

As I finished my spiel, Mihiretu pointed out the window. "Mama," he yelled, "Bus!" Lana said, "Yeah, but Mom, will we get treats at Papa and Nana's?"

But Mae, bless my Mae, looked into my eyes in the rear-view mirror and said, "I feel so lucky, too, Mom, to be your daughter."

And so I live to fight another day.

Later that day, I was in the van with the kids, headed for Ben's dads' house to carve pumpkins. It was a rare moment in the car that they weren't screaming at each other or swinging fists so I took advantage of the seat-belts holding them in place, my little captive audience, and told them about Ingrid Betancourt and what she had learned. And I told them that the one thing in my life that makes me happiest, by far, is being their mother. I may complain, I may get grumpy, I may even yell but always, underneath it all, I'm so grateful to be able to be home with them, to nurture them, to watch them grow. Them, particularly, those three disparate, complicated creatures. That I'm lucky to be their mom.

As I finished my spiel, Mihiretu pointed out the window. "Mama," he yelled, "Bus!" Lana said, "Yeah, but Mom, will we get treats at Papa and Nana's?"

But Mae, bless my Mae, looked into my eyes in the rear-view mirror and said, "I feel so lucky, too, Mom, to be your daughter."

And so I live to fight another day.

Thursday, November 4, 2010

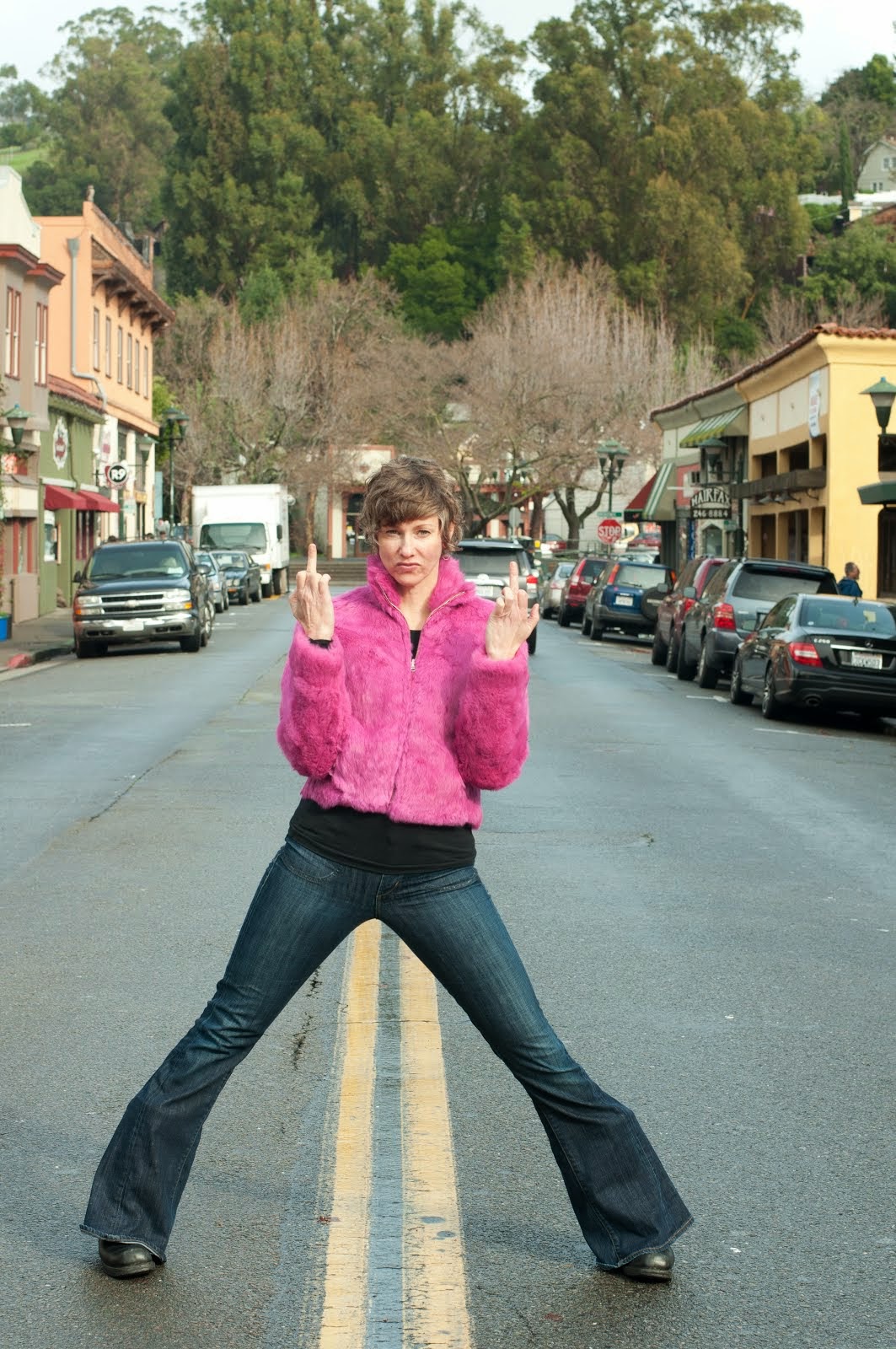

A Blue Streak

On the last page of Vanity Fair every month is "Proust's Questionnaire", in which some celebrity (Shirley MacLaine! Gore Vidal! Liza Minelli!) answers an identical list of queries. "What's your favorite journey?" ("New York to Paris, unquestionably") "What do you most value in a man?" ("Courage, strength and a sense of humor") "What do you most value in a woman?" ("Beauty, grace and a sense of humor") and my very favorite, "What's your most overused phrase?"

To that, I realized the other day, after trying to thread a needle three times unsuccessfully, my own answer, were Vanity Fair ever to come calling, would be "God fucking damn it." I say it a lot. Mostly in my head or at least under my breath, but a lot. Almost any time I'm confronted with frustration great or small, my first response is "God fucking damn it" before I plunge in and try to right the wrong.

It's a ridiculous collection of words. What does it mean, beyond stringing together as much blasphemy as possible? Packing in the foul? But, for whatever reason, when I'm faced with the kid's dirty, discarded clothing on the floor of their bedroom or a duvet I just put on the comforter inside-out, or a trail of small, muddy footprints leading from the front door down the hall, it's somehow satisfying, somehow comforting to unleash this particular compact package of profanity.

I was washing the dishes the other day - it seems like I'm always washing the dishes - when a glass slipped out of my pink rubber-gloved hand and shattered in the sink. "God fucking damn it," I breathed. Lana, puzzling through her math homework at the counter looked up in surprise and amusement. I grinned at her. "Silly, right?" I said, "Silly thing to say?"

"God fucking damn it", she said, grinning, too, abandoning her arithmetic to retrieve a paper bag in which to put the shards.

To that, I realized the other day, after trying to thread a needle three times unsuccessfully, my own answer, were Vanity Fair ever to come calling, would be "God fucking damn it." I say it a lot. Mostly in my head or at least under my breath, but a lot. Almost any time I'm confronted with frustration great or small, my first response is "God fucking damn it" before I plunge in and try to right the wrong.

It's a ridiculous collection of words. What does it mean, beyond stringing together as much blasphemy as possible? Packing in the foul? But, for whatever reason, when I'm faced with the kid's dirty, discarded clothing on the floor of their bedroom or a duvet I just put on the comforter inside-out, or a trail of small, muddy footprints leading from the front door down the hall, it's somehow satisfying, somehow comforting to unleash this particular compact package of profanity.

I was washing the dishes the other day - it seems like I'm always washing the dishes - when a glass slipped out of my pink rubber-gloved hand and shattered in the sink. "God fucking damn it," I breathed. Lana, puzzling through her math homework at the counter looked up in surprise and amusement. I grinned at her. "Silly, right?" I said, "Silly thing to say?"

"God fucking damn it", she said, grinning, too, abandoning her arithmetic to retrieve a paper bag in which to put the shards.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)